The need for more space

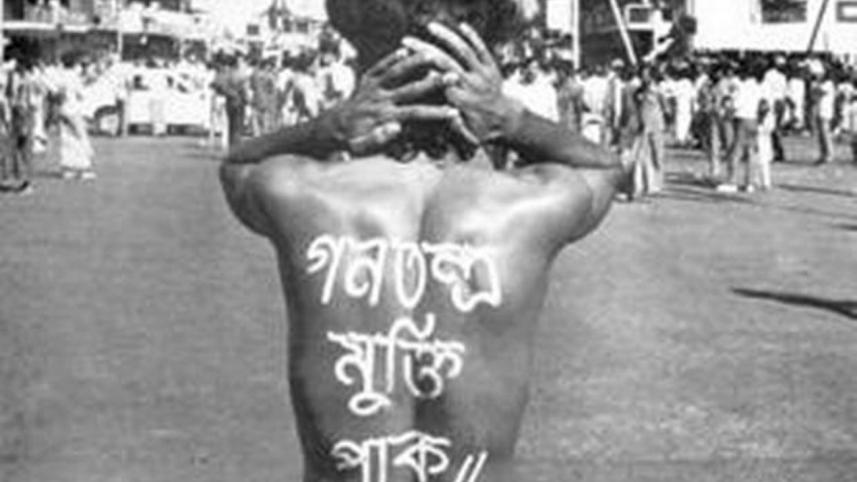

During the US Civil Rights movement in the 1960s, Dr. Martin Luther King had said, "Riot is the language of the unheard." How pointingly Dr.King had referred to the utmost significance of the freedom of expression in a democratic society. It is an irony that such remarks had to be made to the address of a state which proclaimed in its Declaration of Independence back in 1776 that, "All men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." The paradox of this society becomes all the more evident when one remembers the historical Four Freedoms Speech of President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered in 1941, in which he unearthed the basic principles based upon which a new world order would be established after World War II. He considered 'freedom of speech and expression of every man anywhere on the globe' as one of the fundamental four freedoms. Today, it is universally recognised that freedom of expression is integral to democracy in the same manner as human rights cannot be enjoyed, ensured or nurtured in the absence of democracy. Thus, human rights and democracy are interdependent and mutually inclusive.

However, one might ask what are the modalities of 'freedom of expression' and as is the case with any freedom or right, who are the 'right-holders' and who are the 'duty-bearers'? Whereas the ultimate duty-bearer in all human rights is the state, the rights-claimers may be an individual, a group or even the whole society. While the first two categories of rights-holders do not create any confusion, 'society at large' as the rights-holder leads to various interpretations and even certain confusions – who represents the society? Political parties? Elites? Intelligentsia? Professional groups? Trade Unions? NGOs? Or is it the 'civil society'? Without going into an analysis of each of these categories (concepts), we need to acknowledge that each of them enjoys a certain degree of space in representing the 'opinion' of their respective groups. In certain circumstances, this 'group opinion' may be identical to the 'public opinion' defined as the aspirations and expectations of the overwhelming majority of the population. Despite certain reservations, it is commonly believed that the civil society is the bearer of public opinion and hence, the role of the civil society becomes crucial for democratic governance.

Fukuyama wrote that "democracy has taken hold as the result of the power of the underlying idea of democracy." The idea of human equality that underlines modern democracy is also the fundamental essence of modern concept of human rights.

Democracy may also be understood not merely as the expression of an idea or a set of cultural values but as the by-product of deep structural forces within societies. Social scientists have long noted that there is a correlation between high levels of economic development and stable democracy. For economic development to touch upon 'human development', democracy is indispensible. And for democracy to flourish, space of and for the civil society must be increasingly extended and expanded. In a contrary situation, political decay is the inevitable consequence.

It would be unfair to expect that all civil society actors will possess identical views on different social or political issues. Pluralism is the soul and beauty of democracy. However, pluralism cannot sustain if the duty-bearer, i.e. the state is not tolerant to different, even opposing views. Peaceful coexistence of different and opposing views is the precondition of freedom of expression. It is now common wisdom that no freedom is a license – my freedom ends where your freedom begins. It is also universally accepted that the state, in greater public interest, may impose certain restrictions on freedoms enjoyed by its nationals, including the members of the civil society. This sovereign right of the state must in no way be construed as a power to put restrictions and shrink democratic space of the civil society merely on the basis of 'subjective factors'. The state must never lose sight of the fact that its suspicion about any civil society actor posing threat to 'national security', or 'jeopardising greater public interest', must be based not on subjective but only and exclusively on objective grounds. Even subjective satisfaction of the executive must be based on objective factors! Modern notion of human rights demands such a high standard of democratic practice by the states - the duty-bearers.

The rights-holders (the civil society, for example) on their part should similarly acknowledge that while any move by the state to shrink their democratic space is not commensurate with either democratic governance or human rights, they also have a duty not to 'abuse' their right to democratic space providing various freedoms and liberties. In the same token, tolerance to opposing views does not necessarily guarantee freedom to oppose the prosecution of crimes against humanity, crime of genocide or resorting to bloody violence, arson, destruction of public property, throwing of petrol bombs or indiscriminate killings. Mahatma Gandhi once said, "War cannot be the path for peace. The path for peace is peace itself." We can echo the same: Democracy cannot be established through undemocratic means, human rights cannot be ensured through denial of democracy, and freedoms cannot be guaranteed by shrinking the space of human rights defenders, whether natural or artificial.

The writer is Chairman, National Human Rights Commission (JAMAKON), Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.