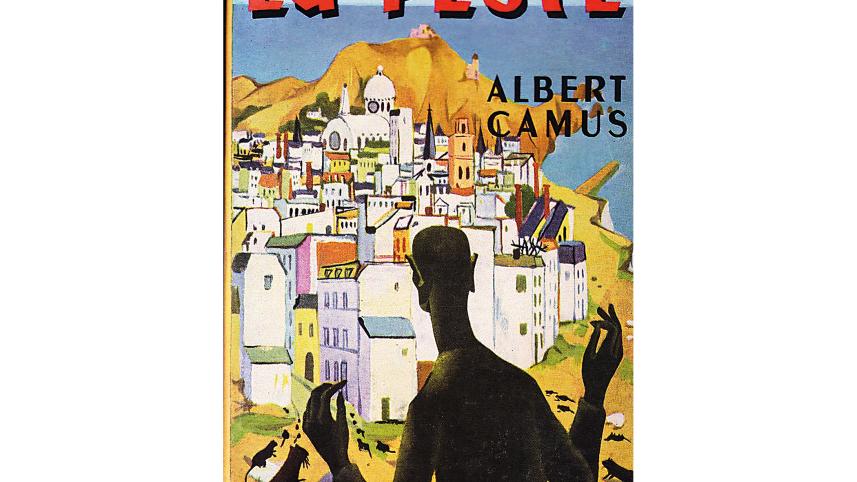

CAMUS REVISITED

One intriguing question in Albert Camus's philosophical novel "La Peste" (The Plague) is the idea of death perceived through the sense of rationality. The town where Camus placed his events is the Algerian town named Oran. The beauty and sublimity of Oran by the sea giving intense desire for life was brought to a halt by a sudden onslaught of an epidemic. It was the sighting of a dead rat one morning at the landing of his surgery that Dr Bernard Rieux, the main character of the story, found so genuinely unsettling and life-threatening. Camus's strategy to create a crisis out of a small-town incident has given Oran a place in literary discussion.

In a way, Oran foretells the story of Wuhan, the Chinese town held responsible for the onset of COVID-19. The fear is not whether Camus' hypothetical Oran suffered less or the real Wuhan lost more lives; the pain and angst to human existence is exceptionally profound. While Camus's plot could never allow the spread of the disease beyond the defined perimeters of the small town because he did not want the integrity of the story to overwhelm his literary capacity, the Wuhan virus has crossed beyond its borders to the whole universe. Oran's epidemic in its mythical sense fulfills the narrative of an all-engulfing disease with a strong sense of defeat and self-abnegation. Was COVID-19 something that could have been stopped, the way Camus felt that Oran could be saved from so many deaths if authorities took actions at the right time? But nature always plays its card much faster than the human intellect can muster its resources. Like the weak feel helpless when facing the strong, so does man by the strike of a powerful invisible object that frequents from time to time to remind man of his abject reality.

There are striking similarities in how Camus developed his story, and how the world faces the COVID-19 today. Camus saw, in the midst of great fear and panic, a group of people whose sense of direction in facing the plague was sometimes fatuous and imprecise, but there was no denying of their commitment to social obligation. Dr Bernard Rieux stood in the centre of professional acts defying the beleaguered temptation of a frightened population. Being a doctor, he lost the critical temperament of a physician, and understood that it was necessary to restore in him an air of sang-froid in times of hardship. In other words, the plague transformed him into a complete man indifferent to the will of ordinary people. So, when he heard the death of his wife who was sent away to a sanitarium for recuperation and whom he had not seen since the beginning of the plague because Oran was put under quarantine, he received the news with grace and perfect equanimity. When life ends under normal circumstances, it has a meaning in genesis, but when plague ends life, it assumes a sense of deprivation sunk in absurdity.

The characters in the Plague were all affected by its ravages. The physical death was merely an appearance of long-drawn futile struggle with an intractable curse, unwieldy, stubborn and procrastinating. The hollow part of human suffering was the mental shock and devastation it orchestrated in the community life of Oran. Oran's grace and beauty was embalmed by its landscape, the soothing effulgence of the sun in a naked sky and the winding streets meandering their way to the fringes of the inviting Mediterranean coast. There was enough for ordinary folk to explore into Oran's rich heritage of happiness and contentment --- sun, sky, sea, mountains, cafes, sports ----the everyday but unstoppable offering of life which the inhabitants loved immensely. All came to an end with the sudden outbreak of the plague for which the innocent people were least prepared.

The first thing that the authorities of Oran did was to isolate it from the rest of the world. Its borders were sealed to prevent entry and exit of people into and out of Oran. This was a usual measure under nervous faculty. When good decisions are in short supply, the only way to react is to make the predictable ones look urgent and authoritative. Oran was walled and the purpose was to imprison the citizens in their own city. The natural effect of such official measure was to imperil the human condition. It could not stop the death row in the hands of an invisible assassin, adept in being crueler and more dangerous than the senseless orgy of maskless killing in a war. When soldiers die in a battlefield, their burial becomes a symbolic celebration of an absurd cause for which their lives were committed to extinction.

In The Plague, Camus shows that the continuous procession of deaths without redemption in the initial months of the epidemic held every one in suspense whether the next victim would be himself. If not, then lack of work owing to closure of the outside world because of quarantine was cruel enough to consign one to unemployment, a situation more dreadful for living than contracting plague. Plague, as a metaphysical enemy, is not only content with killing but also raises the act of "mass death sentence" to a reprehensible level of depravity against ultimate human condition. Poverty, as a practical adjunct to such calamity, shows itself as a greater evil than fear of death.

But Camus's novel must not be read as a straightforward narrative of a fictional story. Read on a philosophical plane, it presents man's struggle against his unpredictable destiny. Dr Rieux is not alone in his fight against suffering and death. There are few other characters for whom self-sacrifice in times of epidemic was a conscious moral objective.

Jean Tarrou, an inscrutable enthusiast who created sanitary squads to stop the town from being infected rapaciously; Joseph Grand, a clerk aspiring to be a writer kept records of the deaths till late into the night with self-righteous accuracy; Dr. Castel, an elderly physician, labored vigorously to produce an effective serum against the plague; Father Paneloux, a clergyman, led the evangelical sermons in the expression of Saint Augustine believing in the emergence of evil in the form of punishment as a result of sin committed by man, and saw in the plague God's pointing to the citizens of Oran for eternal salvation; the Prefect of the town, as an administrator, lay about all possible actions, right or wrong, to come to grips with the epidemic; and above all, Madame Rieux, the doctor Rieux's mother, who despite his son's unflinching loyalty to the cause of fighting the plague, never for a moment doubted that her son could be an easy victim of the scourge, yet bore with his work as a woman dedicated to the canon of sainthood. These were ordinary people in their extraordinary role that makes the novel so gripping and ethereal.

The plague lasted for about a year. The city came back to its fresh start. The exile and deprivation that the plague had occasioned upon Oran went away with the tears for the lost ones, and in its place, an ineffable joy had suffused the souls of the suffering mass. The finality of death, which decided the key argument in The Plague, serves as a weak point of man's strength. Camus ends his novel by letting Dr Rieux declare that the "plague bacillus never dies or disappears for good" and when occasion arises out of man's control, rats can once again rouse up to usher in "death" in "a happy city for the bane and enlightenment of men."

The Plague presents the symbolic context which the nations find themselves in today. Camus's fictional plague was a localized phenomenon confined within the walls of Oran, whilst COVID-19 engulfs the whole of mankind. The majesty of the novel, the Plague, is in art form, and raises human catastrophe to the level of an idea whose words and thoughts continuously swing between mystification and truth. As an ordinary soul, upon the misery of COVID-19, I have reread the Plague with the commitment of a soldier challenging death in a battlefield. If only we could read Camus's novel as a lesson for collective bargain, we could say in the words of book title of Debora Mackenzie, "COVID-19: The Pandemic That Should Never Have Happened and How To Stop The Next One."

Camus teaches a number of practical lessons to us. He equates war and plagues by asking why they occur. Digging into these philosophical questions with an impersonal but highly moralistic mind, he notes how life, in pure and abstract form, represents two different things. The beautiful world lives in poetry, music, painting, mathematics and religion. It is the pathos of the immediate and most provisional that frames the tangible world's existence in absurd hypothesis.

The Plague is a reflection of man's continuous struggle on moral, physical and intellectual plane. A reader will only fathom its value if he seeks man's true worth as an object of nature --- and it is "love." No matter how difficult it is, man will continue to imperil his existence to protect the same existence to give meaning to his love of birth as a rational being. If the entire human race is condemned to the orgy of COVID-19, it is only a matter of time that it will be over one day through man's undoing of the virus, and affirming himself as a stronger object in his triumph over evil.

Mahmud Hussain is retired Air Vice Marshal and former High Commissioner to Brunei.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.