Cages of flesh and bone: Deconstructing social hierarchies with

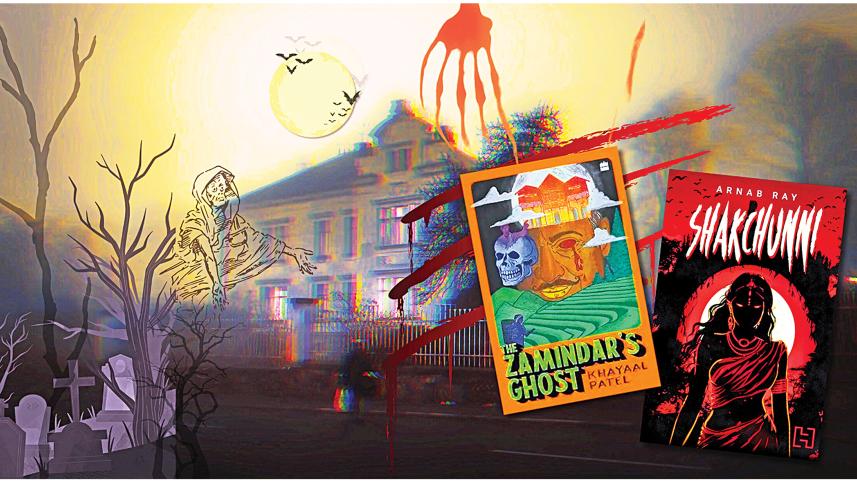

In the mist-covered hills of Ooty and the famine-ravaged villages of Bengal, they speak of ghosts. They whisper of a Zamindar's phantom haunting a grand manor and a shape-shifting shakchunni preying on a crumbling estate. But to listen only to these whispers is to be deceived. For the true horror in Khayaal Patel's The Zamindar's Ghost (HarperCollins India, 2023) and Arnab Ray's Shakchunni (Hachette India, 2024), it does not lurk in the shadows of the supernatural; instead, it thrives in the broad daylight of social hierarchies. These are not mere ghost stories.They are chilling portraits of the real, breathing monsters we create—the gilded cages of class, the suffocating weight of patriarchy, and the brutal machinery of colonial power. The phantoms are a smokescreen, a folkloric language for a far more terrifying truth: that the most malevolent hauntings are the legacies of injustice etched into the very foundations of society.

In Ooty, the legend of the Zamindar's ghost is a convenient fiction, a collective lie the town tells itself. It is easier to blame a restless spirit for the death of the Zamindar's loyal servant, Rai Bahadur. He is a tragic ghost, a man who sacrificed his family on the altar of loyalty to the Rana family. His life is a lesson in the cost of servitude within a rigid hierarchy, a lesson his son, Tej, the head constable, has learned through a lifetime of neglect. Tej's hollowed-out existence is a living tomb to the human price of maintaining an unjust order. This order, however, is not self-sustaining. It is a tool, crafted by the British Raj. The Zamindars, such as Digvijay Rana and his son Arjun, are not just powerful landlords; they are local elites empowered by the Crown to exploit their own people and maintain control over them. The system's most profound cruelty is forcing the oppressed to participate in their own subjugation. Arjun Rana's torment over leading British troops against his own people is the ultimate colonial trauma—a haunting that no exorcism can dismiss, a ghost that walks in the uniform of the oppressor.

Ultimately, the supernatural in both novels serves as a desperate language, a means for characters and communities to articulate a trauma too vast and too brutal to be named. The political is not a subplot; it is the very air these characters breathe, thick with the poison of oppression.

A similar decay oozes in the heart of Shyamlapur, the setting of Arnab Ray's Shakchunni. Here, the feudal hierarchy is not just a social ladder but a death trap. As the Great Bengal Famine—a man-made catastrophe driven by colonial policy and local greed fueled by materialism—the zamindars of the Banerjee family hoarded grain in their granaries. Their lavishness is a stark, grotesque contrast to the villagers, who scavenge in drains for survival. This oppression is not merely external; it replicates itself within the manor walls. The patriarch rules through a pathetic tyranny, while his sons, Narayanpratap and Rudrapratap, are pitted against each other by their parents, a chilling demonstration of how a system maintains its power by setting the oppressed against one another. The novel poses a distressing question: Who is the true monster? The folkloric 'Shakchunni' spirit that demands occasional offerings, according to the famished villagers or the aristocrats who systematically consume the lives, dignity, and future of an entire population? The supernatural entity is merely a symptom; the disease is the hierarchy itself.

Within these oppressive structures, the lives of women become a brutal battleground where the agency of women is a forbidden fruit and identity is a ghostly, borrowed thing. In Ooty, the patriarchal order is metaphorically enforced by the ever-present rumour of the Zamindar's ghost. Archana Rana is its tragic prisoner. Married into the Rana family in an alliance that swallowed her father's fortune, she is trapped in a gilded cage. In stark defiance stands Sharvani Mehra. She navigates the same patriarchal world not as a victim, but as a rebel, weaponising male desire to carve out a sliver of freedom and influence. Yet, her defiance comes at a cost—a life of societal judgment and isolation, a price exacted by the very hierarchy she subverts.

Shakchunni takes this theme of female identity and makes it the core of its horror. The very myth of the shakchunni—a female spirit who possesses a bride to steal her life and her home—is a perfect metaphor for a system that erases a woman's identity, making her a mere vessel for male legacy. The young bride, Saudamini, is not a person but a transaction, married to a heartbroken man and valued only for her potential to produce an heir. Her mother-in-law, Bouthakurun, is perhaps the most terrifying character of all—a woman who the patriarchy has so thoroughly consumed that she becomes its most vicious enforcer, ensuring the next generation of women endures the same subjugation. The absolute horror here is not a ghost, but the grotesque, predatory lust of Raibahadur for his own daughter-in-law.

Ultimately, the supernatural in both novels serves as a desperate language, a means for characters and communities to articulate a trauma too vast and too brutal to be named. The political is not a subplot; it is the very air these characters breathe, thick with the poison of oppression. In The Zamindar's Ghost, Tej's absurd obsession with a "Revolutionaries' spy" is a classic case of misdirection, closing his eyes to the corruption brewing within the system he is sworn to protect. Digvijay Rana's ghost can be viewed as the lingering spirit of colonialism itself, a violent, decaying presence that continues to demand sacrifice. In Shakchunni, the haunting is directly fueled by the Great Bengal Famine. The crumbling estates, the rising communist ideals among the desperate, and the heavy hand of the British Raj create a pressure cooker of societal collapse. The 'shakchunni' is the folkloric embodiment of this collapse, a scream of anguish given form, a story told to make sense of a world devouring itself.

To read The Zamindar's Ghost and Shakchunni as simple ghost stories is to miss their profound, beating, and broken hearts. They are historical critiques dressed in the chilling costume of folklore. They force us to look past the ghosts in the window and into the darkness of our own histories, to recognise the terrifying reflection staring back. The accurate spirits are not the undead, but the inescapable, man-made structures of social hierarchy—the chains of class, the prisons of gender, and the legacy of colonial power. These are the monsters that outlive their creators, haunting the halls of manors and the hearts of villages long after the bodies have been buried and the ghosts, supposedly, laid to rest.

Nazmun Afrad Sheetol is an IR graduate and a writer for Substack. She can be reached at sheetolafrad@gmail.com.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments