The death of the film and the rise of its maker

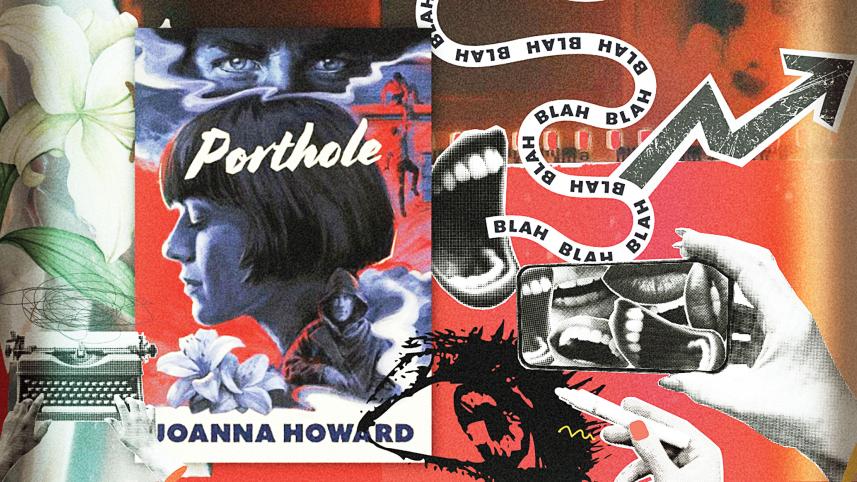

Novels that explore the life of a filmmaker are few and far between. When I think of a film, it's usually the actors that are at the center of my attention and more and more recent novels attest to that.There's a more widespread interest about an actor's life—with all kinds of rumors and lies and gossip that abound in their elusive world—than let's say a quirky filmmaker, which is why the latter doesn't make it into gossip culture—at least not as often as actors do. However, Porthole by Joanna Howard is an exception, and its exceptionality starts with a nuanced unearthing of a filmmaker's troublesome past, Helena Désir, also an unreliable narrator who tells her story with a subdued humour that is neither cliché nor overdone. Howard's narrative is so full of hidden truths about filmmaking that have remained, up until now, behind the camera lens and crystal liquid.

The death of an actor named Corey and an abandoned film begins the book. However, Helena's real trouble seems to have started way before that, with her very childhood that is atypical, as she was raised by her somewhat libertine uncle (or an "enfant terrible" as Helena calls him) who lived his whole life on a boat called Anjodie and had a tremendous impact on her. This loose upbringing impacts all her relationships with future actors, some of whom turn out to be her lovers. And again, it is on a boat, while working on a turbulent film, whose story climaxes when a man attempts to kill his wife's lover by taking him out on a riverboat, that a tragedy ensues in the novel, killing Corey with whom Helena had an emotional entanglement, paralleling the plot of the film she's making. And eventually this tragedy, this death, compels her to postpone her filmmaking and to seek help from a professional at Jaquith House, a splashy retreat where she meets a host of other people recovering from "psychic exhaustion."

The death of an actor named Corey and an abandoned film begins the book. However, Helena's real trouble seems to have started way before that, with her very childhood that is atypical, as she was raised by her somewhat libertine uncle (or an "enfant terrible" as Helena calls him) who lived his whole life on a boat called Anjodie and had a tremendous impact on her. This loose upbringing impacts all her relationships with future actors, some of whom turn out to be her lovers. And again, it is on a boat, while working on a turbulent film.

It is at Jaquith House—which for a good reason reminded me of Liane Moriarty's Nine Perfect Strangers (Flatiron Books, 2018)—Helena questions the nature of her reality, including her pen name, the one that she uses to tell her story. She speaks aloud and often tries to break the fourth wall: "Was I speaking?" "What was I saying? Again! The order…" "What did I say, I wonder? The fact is some conversations escape me like mist." All these incoherences add to the narrative tension. It forced me to ask how much I should trust her, just as Helena asks herself while seeking help from Dr. Duvaux. But of course the doctor takes his sweet time (there's a significant claim by another character that the doctor may not even be a real doctor!) and seems rather interested in her past, and in particular in goading her back into filmmaking. Cash-strapped, the doctor has a real incentive to heal this special patient in order to help his failing business back on its feet, with a promise from Helena's studio who wants her to finish the film. It turns out, it is not the doctor but her fellow "sufferers" at the retreat that contribute to her recovery. It is in the association of such people: a creepy and sex-crazy chef, an uberrich entrepreneur, a mysterious caretaker, among other zany ones, that Helena could distance herself from her past, her art—and can see everything afresh.

During her career, she mostly worked with a trio: Emile, David, and Corey, all more or less her own discovery, her reinvention. But the idea of a reinvention, in this highly gendered world of filmmaking, troubles them and they all fight with Helena, although she knows how to put everything behind as soon as she looks through her camera, telling her doctor candidly that the "the camera objectifies" and that she is "just the messenger." The actors disagree with this classification while falling in and out of love with Helena, some coming back again and again until they realise the tenuous nature of their romance. Of these three, perhaps David is more memorable. One example will suffice: when Helena berates him for talking as though he's copying lines fr

ILLUSTRATION: MAISHA SYEDA

om a script, he says, "I have an enormous arsenal of memorized lines. I never have to think of anything original to say again." At one point, she confronts both David and Emile and laments that perhaps she shouldn't let the lovelies meet, just as her uncle advised her years ago, but apparently that is something beyond her control. Written with an incredibly light pacing, the chapters in this novel have a pendulum-like balance that start and end at a predictable point, which made it easier for me to go through its otherwise difficult subject matter—filmamking and a director's relationship with actors. Perhaps it is this exceptionality of dealing with the complex world of film—and I mean it positively—that the book excels at, bringing to mind the fast-paced, curiosity-driven writing of Haruki Murakami. And even Susan Choi, whose Trust Exercise (Henry Holt and Co., 2019) is a great comparable title.

Much of what a writer makes comes from the materials she has processed a long time ago, which seems to be the case here as well. Joanna Howard, who teaches creative writing at the University of Denver, has written books about international romps and romances, including her book Foreign Correspondent (Counterpath Press, 2013) that has a similar protagonist and the book itself is inspired heavily by the work of Alfred Hitchcock. Her current novel under review seems to be a culmination of these past experiences, and I love the fact that this book has a deep conversation with her previous work. It is as though the book decided to write itself, a self-awareness that guides and propels the narrative organically. My favorite lines in this book lie somewhere along this theme: "A career has a life of its own. The more you direct it, the less it is likely to comply." An aphorism I fully agree with.

It is in such lines that I can also fully empathise—even identify—with Helena's struggle with making remarkable films or anything whose value is hard to predict. It's a Sisyphean effort that never feels complete even when the work—a film in this case—is out for the public to consume. Even then the artist feels and knows where the weaknesses lie—if any. But perhaps it is for such weaknesses in the production of art that we pardon the artist for whatever crime they committed, whomever they hurt along the way? I have mulled over this question as I put down the book, which also wants us to ask what happens when we try to be truly authentic through art, through writing. Ultimately, Helena seems to recover and revive herself despite losing faith in her filmmaking, despite convincing herself about the death of film as an art form.

Mir Arif is a writer based in Ohio. A Granta Writers' Workshop alumnus, his fiction and nonfiction have appeared in numerous literary magazines such as Story, Tahoma Literary Review, The Los Angeles Review, Sierra Nevada Review, and many others.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments