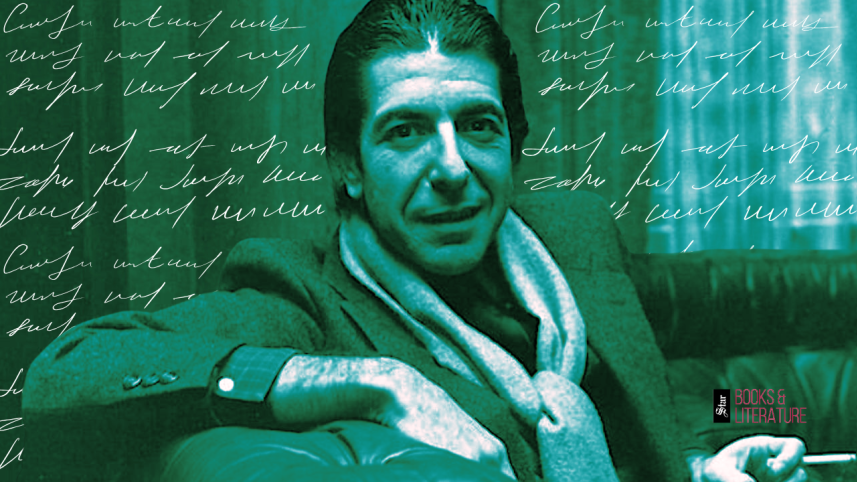

Leonard Cohen: Verses of mercy and turmoil

The anthem of generational melancholy "Hallelujah" may be fundamentally religious in its origin, but it was the lyrical prowess of Leonard Cohen (1934-2016) which turned it into a cultural lexicon. Unfortunately, the song's popularity has overshadowed the poet underneath. Many of his early poetry were the foundation of future songs. Born in an Orthodox Jewish family on September 21, 1934, Cohen's work was profoundly shaped by his spiritual persona. The brilliance in his voice is just as inseparable from him as his fiercely held religious identity. His spirituality is also the reason perhaps, why, it would be a disservice to the man himself to speak about his accomplishment in isolation, considering the ongoing genocide in the Middle East conducted by the very country that shaped his religious heritage.

Before he was "Leonard Cohen—the celebrated singer", he was "Cohen, the poet". With unyielding sincerity, he embarked upon themes of faith, love, reality and mortality with his distinctive lyrical flair.

A visceral form of sensuality, a wry and self-deprecating humour, and a theological solemnness would often blend to form his unique poetic tone. His first book of poetry, Let Us Compare Mythologies (Contact Press, 1956), while amazing, did not credit him with much notable recognition. His second book of poetry, however, helped him reach critical acclaim in Canada's literary circle. This collection, A Spice-Box of Earth (McClelland & Stewart, 1961) would help define much of his artistic legacy, and his ability to simultaneously provoke thought and offence through words with subtle yet unexpected emotional depths was beautifully illustrated through this collection.

To speak of just one poem from this collection is impossible considering how many captivating pieces of his early writing have been immortalised in this collection. Blending the deeply personal with the metaphysical is one of his defining traits of poetic writing, especially during his early days. And this collection beautifully exemplifies that particular trait. He provided a poignant meditation on the enduring and transient nature of love and life in the poem "As the Mist Leaves No Scar". In the poem "I Have Not Lingered in European Monasteries", he celebrates the beauty of living an unpretentious and grounded life. He tenderly delves into the notion of vulnerability and physical intimacy in "Beneath My Hands" and explores the concept of freedom and control and their relation to creativity through the symbolism of a kite's flight in "A Kite Is a Victim".

Any study of his poetic genius, however, would be incomplete without the mention of Book of Mercy (McClelland & Stewart,1984). It is not a traditional form of poetry, more of a blending of prose and poetic verses. Considered by many as a contemporary rendition of the biblical Book of Psalms because of the way it mirrors in style and theme.

Religious allusions aside, this collection is also a candid dialogue between the divine and the author about everything—from doubt, loneliness, and despair to the yearning for the unknown. It's an exploration of Cohen's spiritual resolve that forces us to consider his potential complicity in the decades-long conflict conducted by his home nation.

He once performed for the IDF to boost the soldier's morale during the Arab Israeli conflict in 1973 (known as Ramadan War in Egypt and Syria and Yom Kippur War in Israel). The war was also fought in proxy by the USA and the Soviet Union by the thorough resupply of their Israeli and Arab allies respectively. As for Cohen, it wasn't just a one-time performance. With his trusty guitar, he traipsed all over the desert expanses of the Sinai Peninsula with IDF soldiers. Later on, he supposedly donated much of his concert earnings from Israel to organisations which supported bereaved Palestinian and Israeli families. And yet, monetary donations after cheering on soldiers' march into further bloodshed feel quite a hollow gesture of humanity. Though he did have a much bleaker view of the "Promised Land", later on his life, it still does not erase the mindless allegiance he willingly embraced in his early years. Cohen's unyielding support unfortunately contributed to the collective impaired vision undertaken by the majority world regarding the unfair and the brutal violence faced enforced by the Israeli nation. And that continual blindness has undeniably played a part in the current situation of normalising televising the genocide live but no one doing anything about it.

Everyone speaks, just a little bit too late. Cohen spoke too, just a little bit too late. In Psalm 24 of Book of Mercy, he wrote,

"ISRAEL, and you who call yourself Israel, the Church that calls itself Israel, and the revolt that calls itself Israel, and every nation chosen to be a nation—none of these lands is yours, all of you are the thieves of holiness, all of you with Mercy. Who will say it? Will America say, We have stolen it, or will France step down? Will Russia confess, or Poland say, We have sinned? [...] The land is not yours, the land has been taken back, your shrines fall through empty air, your tablets are quickly revised, and you bow down in hell beside your hired torturers, and still, you count your battalions and crank out your marching songs."

This is one of the rare psalms in the book with such a harsh and accusatory tone. The spiritual and political arrogance of any particular group or nation to claim land, based on supposedly divine rights, is bitterly questioned by Cohen. It is not just a general condemnation; he specifically demands accountability from certain nations. The super-powered America, France, Russia and unsurprisingly Poland—the nations which provided an enormous number of Jewish refugees during World War II who became the core part of the occupying Israeli nation.

Other than some of these small works, he never really declared his stance regarding this issue out loud. Had he still been here, would he have spoken out more? Or would he have stayed mostly silent like his fellow intellectuals and pretended it to be a complicated ancient conflict, not an obvious genocidal campaign instigated and maintained by the powers that be? We can never truly know, but exploration of his works, especially his poetic ones, gives us hope for his humane view.

Tasmia Qazi is a perpetually confused Literature major, who is eternally in love with words.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments