Non-bank interest cap goes against global trends

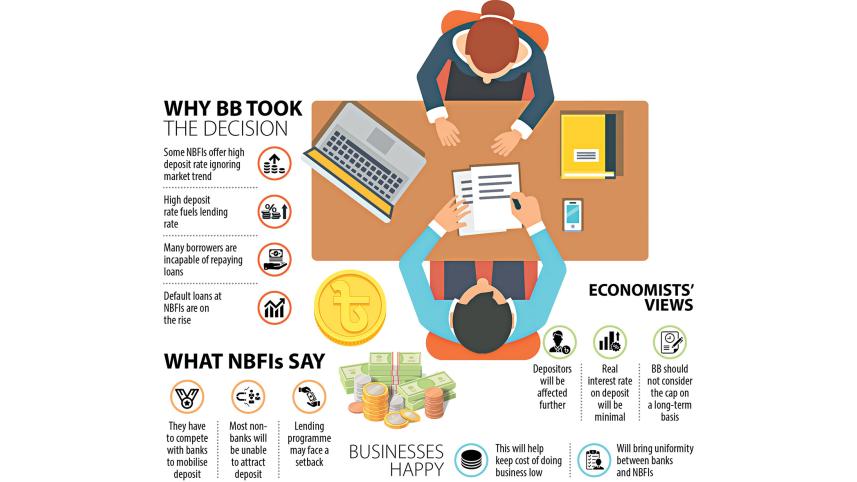

The Bangladesh Bank yesterday imposed an interest rate cap on deposits and loans at non-bank financial institutions aligning with the ceiling now prevailing at banks although rates are rising globally to tame runaway inflation.

So, NBFIs will have to charge a maximum of 7 per cent on deposits and 11 per cent on loans from July 1, according to a BB notice.

The central bank move came two years after it capped the interest on lending at 9 per cent and deposits at 6 per cent for banks, igniting the debate whether such intervention is the right approach as it sidesteps market forces.

The interest cap comes at a time when countries are raising rates to combat inflation. For example, in March, the US central bank approved its first interest rate increase in more than three years.

A number of economists and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have already opposed such intervention.

Economists and top executives of NBFIs say the interest cap would hand a blow to the financial health of the majority of non-banks, which are already struggling to keep pace with banks in mobilising deposits.

Besides, the interest rate cap on deposits will further penalise savers as they have been hit hard by the lower interest rate regime given the upward trend of inflation.

Some NBFIs have recently begun offering interest rates that are higher than the market rates with a view to collecting deposits, the BB said.

The high-interest rates have fueled the cost of funds for the NBFIs. The higher interest rate on deposits quoted by NBFIs has pushed up the lending rate, bringing an adverse impact on borrowers.

As a result, the repayment capability of borrowers has eroded, sending default loans to higher levels and thus bringing negative effects on the entire economy.

The latest ceiling will not apply to the deposits collected before the BB instruction takes effect.

Mominul Islam, chairman of the Bangladesh Leasing and Finance Companies Association, a platform of managing directors of NBFIs, said most banks now mobilise deposits at a 6 per cent interest rate.

"So, NBFIs will face a tough competition with banks to hunt deposits. Many of the non-banks whose financial health is weak will not be able to attract the attention of clients."

If NBFIs can't manage funds, they will not able to lend, said Islam, also the managing director of IPDC Finance.

Kanti Kumar Saha, chief executive officer of Lankan Alliance Finance, says that interest rates should not be fixed as the market forces would determine it.

"Fixing interest rate can't solve the existing problems of the NBFIs."

Mustafizur Rahman, a distinguished fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue, says the imposition of the interest rate would create problems for NBFIs in collecting deposits and disbursing loans.

"The Bangladesh Bank should reconsider its decision on a temporary basis. Many NBFIs are now in a crisis and the crisis will prolong if they can't mobilise funds as expected."

Monzur Hossain, research director of the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies, says the interest rate cap is distorting the overall market.

"Fixing interest rate is not the right approach as it affects the market mechanism. The low-interest rate on deposits will affect savers."

The economist argues that the real interest rate becomes negative if inflation is taken into account.

"So, people will feel discouraged to keep deposits at banks."

Inflation in Bangladesh jumped to 6.17 per cent in February, the highest in 16 months, driven by soaring costs of foods, further eroding the purchasing capacity of consumers.

If inflation is considered, depositors putting their funds at banks are suffering losses.

"A flexible interest regime will be helpful for the market," said Hossain said.

Hossain points out that the problem in Bangladesh is that the interest rate does not decline in Bangladesh once it goes up.

"This is because the banking sector is oligopolistic in nature and large banks dominate the market," he said, adding that the monetary instruments, used by the central bank to influence the interest rate, do not work properly in Bangladesh.

Businesses, however, welcomed the move, saying it would help them manage funds at a lower cost.

"It is a positive move. The measure will help businesses keep their cost low at a time when the prices of raw materials and commodities are high globally," said Md Jashim Uddin, president of the Federation of Bangladesh Chambers of Commerce and Industry.

The interest rate cap on non-banks will also bring uniformity in interest rates in the financial sector as some NBFIs were charging clients higher by borrowing at lower rates, he said.

Jashim, also the chairman of Bengal Commercial Bank, also supported the view that the market should be controlled when needed.

He cited that banks are charging higher rates for foreign currencies at their will.

"I am a chairman of a bank. I am also a businessman. I also should consider the interest of businessmen."

The IMF has repeatedly requested the BB to withdraw the interest rate imposed in the banking sector in April 2020.

It has called for phasing out the interest rate caps on lending and deposits.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments