A Keeper of Our Visual History

It is 1981. A Bangladeshi Masters student in the US visits the Metropolitan Museum in New York. There, in an exhibition called India Festival, he sees photographs from the 1880's – sepia-toned memories, works by photographic luminaries such as Lala Deen Dayal, depicting people and places in an different era. The student is enchanted. Then and there, he decides that when he returns home he will devote himself to searching out and collecting old photographs in Bangladesh.

Fast forward three decades. I am visiting my bibliophile cousin Khokon Bhai in his house in Dhaka. Knowing my passion for photography, he shows me a book that contains many old photographs and historical mementos of Dhaka. Dhaka Club Chronicles (2009) is a pictorial history of the venerable institution founded in 1911. The book is replete with historical photographs, documents, and pieces of history. I look through it with great interest. To my delight, Khokon Bhai gives me the book as a present.

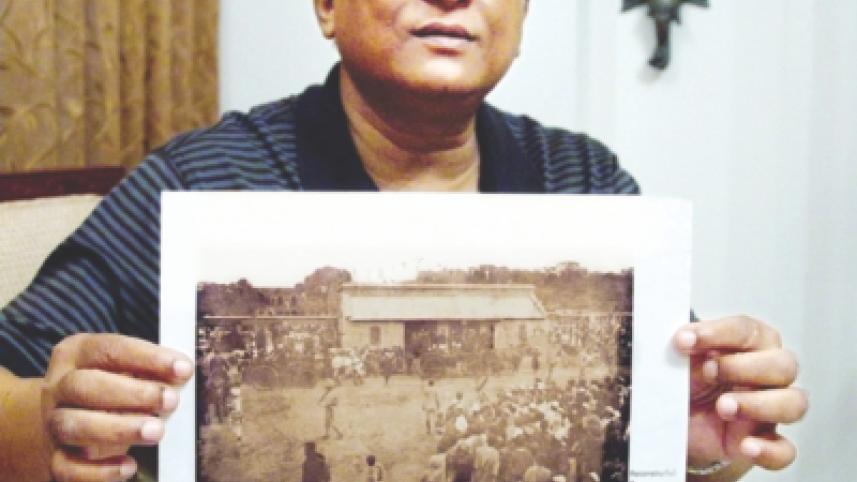

The author of the book is Waqar Khan, none other than the student at the Met. It is his second book. His first, called Rare Photographs of Eastern Bengal, was published by Standard Chartered Bank in 2003 to great acclaim.

Coming home after his studies, Waqar travelled all over the country, meeting patriarchs and matriarchs of old families and convincing them to open up their family albums to him. Over twenty-five painstaking years he has built a collection of 10,000 vintage photographs scanned from various sources. They cover the period 1850-1960.

I ask Waqar about his goal. "I want to build an organised archive of these photographs that future researchers, academics and authors can access. Anyone interested in our history should be able to see these photographs from my archive. For example, the photographs can be used as illustrations in history and sociology books."

I am intrigued by the portraits in his collection. Who were these people? "They were mostly land-owners (zamindars) and the newly emergent middle classes," he says. Then he describes the historical background. Photography became commercially viable very soon after its invention in Europe in 1839, reaching subcontinental shores within a few short months. It created a sensation among members of the local upper classes who wanted their portraits taken. Waqar uses the term "self-memorialization" to express this social phenomenon. The camera's precision in rendering a portrait made it popular. Overnight, portrait painters found themselves in the background.

Much of the action took place in late 19th century in Kolkata, Madras and Bombay, where European photographers such as Bourne and Shepherd set up shop. In Dhaka, the German Fritz Kapp was the only European photographer, working under the patronage of the Nawabs.

Waqar used his contacts not just within Bangladesh, but also in Great Britain and India, while assembling his collection. The historical value of these photographs cannot be overstated. In the Dhaka Club book, for example, I see Ramna turned into a makeshift airfield where Allied planes are refuelling in 1945. I see riders preparing their horses for the Nawab's Cup Horserace in 1892. And I see festival-goers in 1911 celebrating the coronation of King George V at the Dhaka Gymkhana Club. (Mercifully I see no vuvuzelas!)

I ask Waqar for his parting thoughts. "Photography is an art. These images arouse one's senses at various levels. They also provide one with indispensable historical, visual and social insight." Indeed, his illuminating work is an effort worthy of our highest praise and support.

www.facebook.com/tangents.ikabir

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments