Radio Days

The small wooden table sat on one corner of the drawing room. On it was an imposing box the size of a small suitcase. Beige cloth of rough texture covered the top half of its front. Beneath the cloth was the important area: two dials on each side separated by a glass panel with numbers written along its length. When you turned the left dial, a vertical red bar moved horizontally along the panel traversing the numbers. The right dial was a volume control.

That was my first radio, a fixture of the house I grew up in. When war broke out between India and Pakistan in 1965, this radio was the center of nightly gatherings of my extended family. My father operated it every evening so we could hear the news. As he slowly turned the left dial, the red bar traversed the panel and the speaker hummed, crackled and whistled until reaching the frequency of either Radio Pakistan or All India Radio. At that point magic happened: you heard spoken words or music.

This oversized radio was an old engineering design, relying on vacuum tubes that glowed, sometimes overheated and broke down. It was heavy and needed to be plugged into electricity. The tubes were eventually replaced by transistors which were smaller, consumed less energy, and remained cool. In the late 1960s by father bought a lightweight, battery-operated, portable transistor radio and the old vacuum tube radio was soon forgotten.

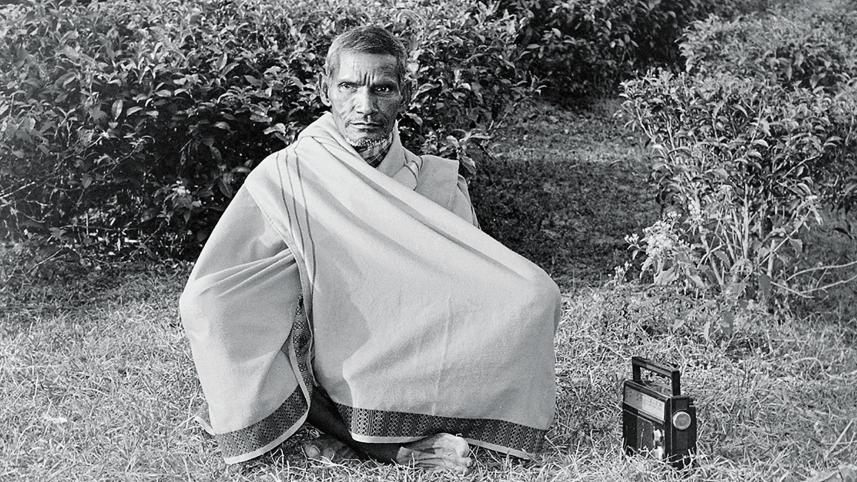

My coming of age was inextricably tied to the radio. During the Liberation War of 1971, it was a critical link to the world. We spent five of the nine months of war in a remote village in Sylhet, taking shelter at my grandmother's ancestral home. Grateful for the safety of our pastoral refuge, we nonetheless missed modern amenities. But we did have a radio. After sunset we eagerly waited for news from British Broadcasting Corporation, All India Radio, Voice of America, Radio Moscow, and most importantly, Shadhin Bangla Betar Kendro, the secret radio station of independent Bangladesh. When M.R. Akhter Mukul read Chorompotro , a monologue rich in humour and bravado, its tales of the success of our liberation forces and the disasters plaguing the enemy emboldened us and made us laugh during those dark days.

After independence, as a teenager I veered towards music and foreign stations on the radio. One day I was listening to shortwave when I heard a new term: "DXer." I was intrigued. Turned out, DX-ers were dedicated radio listeners, scanning the frequencies, searching for radio stations from afar. When you found one, you wrote a letter to the station with the time, frequency and content you had heard. In return, the station sent you a colourful postcard (QSL card) confirming that you had indeed heard the station. DXing proved to be an absorbing hobby for me and I collected hundreds of QSL cards.

My interest in radio changed when I went to London for studies. I now sought out the best radio stations for rock music. One was Radio Caroline broadcasting from a ship in the high seas outside British jurisdiction. It was free of influence of record companies or the government, playing song after good song.

My next move was to the US in 1977. Although FM radio - offering high-quality stereo sound - was popular there, I never quite engaged with it. That was the end of my radio days.

www.facebook.com/ikabirphotographs or follow "ihtishamkabir" on Instagram.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments