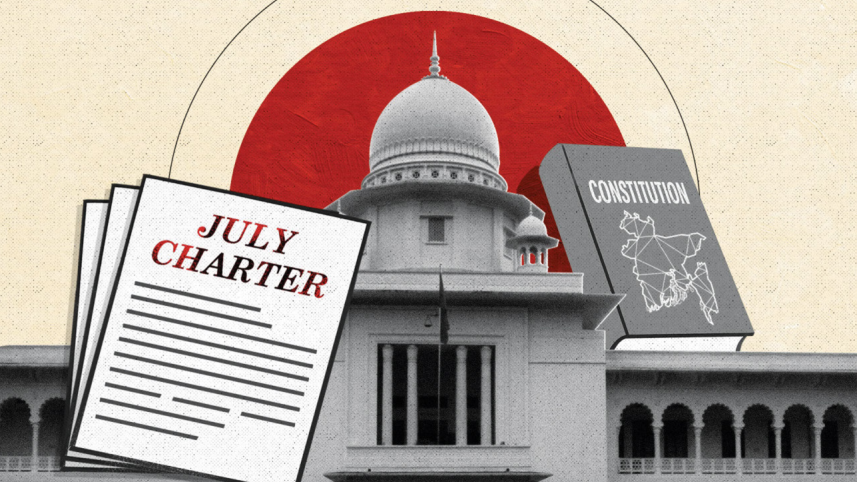

Signing without consensus: Will the July Charter deepen division?

The interim government is organising the signing of the July Charter on October 17 and has distributed the document to all political parties three days in advance. The Charter makes it clear that the process undertaken over the past three weeks to clarify how implementation would proceed has failed, and the question of how constitutional reform will actually take place has become even more obscure.

The Commission has stated very plainly that the signatories will implement the reform proposals written in the Charter. However, they have refrained from explaining how this implementation will be carried out.

The main problem with implementation is that, out of the 84 proposals in the Charter, full consensus among all participating parties in the Commission has been reached on only 28. Among these, the highly impactful reform proposals include limiting the prime minister's term, allowing the opposition to chair standing committees in parliament, separating the judiciary from the government's administrative branch and establishing a separate secretariat for it, appointing a neutral election commissioner, and creating an independent police commission. Additionally, although there are notes of dissent regarding the use of Article 70, if even the agreed-upon portions are implemented, it could be a big step towards making parliament functional.

Since all sides have agreed on these 28 proposals, one might assume that implementing them will be easy. But the reality is that there is no consensus among the parties on how to implement them. Although there is agreement that these proposals should be put to a referendum, there is no consensus on how that referendum should be called. Therefore, even if all parties sign the Charter, implementation of the fully agreed proposals will not occur until they reach a consensus on how to hold the referendum.

The major problem, of course, lies with those proposals where parties have clear disagreements or have submitted "notes of dissent." There are seven proposals that have met with outright opposition from more than five parties. One of them—removing the March 7 Speech from the Constitution—has been opposed outright by nine parties. Seven parties have objected to the proposal to establish three separate commissions.

The main problem with implementation is that, out of the 84 proposals in the Charter, full consensus among all participating parties in the Commission has been reached on only 28.

The largest party, BNP, has objected to fifteen proposals. Among these, nine proposals are also opposed by the NDM, the 12-Party Alliance, and the Nationalist Like-Minded Alliance. Only four parties have raised no objections at all: the Islami Oikya Jote, NCP, Gono Sanghati, and Bangladesh State Reform Movement. On the other hand, the parties with the highest number of objections are BASAD (16 proposals), BNP (15), and the 12-Party Alliance (13).

However, the real fault line lies in the proposals that have drawn "notes of dissent." These include issues such as the powers of the President (objected to by nine parties), the method of forming a caretaker government (seven parties), allocation of seats in the Upper House based on voting ratios (seven parties), and the procedure for appointing constitutional officers such as the Ombudsman, Auditor General, and Public Service Commissioners (also seven parties). Interestingly, on almost every issue where the BNP has lodged a note of dissent, the NDM, 12-Party Alliance, and Nationalist Like-Minded Alliance have aligned with them in opposition.

The problem with these direct objections and notes of dissent is that if any of these proposals are implemented unilaterally, the political climate of the country will become inflamed, and doubts will arise about the next election. Nearly all political analysts believe that if the election is delayed, Bangladesh will head towards instability.

Thus, by failing to specify the path of implementation, the July Charter has placed Bangladesh in a precarious position. The interim government and the Consensus Commission must understand that rushing constitutional reform could plunge the country into grave danger, and recovering from that could take a decade.

They must also remember that consensus must be reached with the dissenting parties, not without them. The time required for such consensus-building must be allowed.

To manage the current situation, organising a referendum could be a solution. Within the Commission, there was majority support for holding the referendum on the same day as the election. This referendum should focus only on those proposals in the July Charter that have achieved full consensus.

For the proposals that have generated disagreement or notes of dissent, a long-term solution should be pursued. To this end, a long-term Constitutional Reform Assembly could be established. To ensure national unity, this assembly could include representatives from different classes and professions, similar to the Legislative Assembly of 1937.

Although there is agreement that these proposals should be put to a referendum, there is no consensus on how that referendum should be called. Therefore, even if all parties sign the Charter, implementation of the fully agreed proposals will not occur until they reach a consensus on how to hold the referendum.

This body could comprise those elected in the forthcoming national election who will form the next government, alongside representatives of the parties that took part in the Consensus Commission, as well as women, members of civil society, professionals, religious minorities, and non-Bengali representatives. The Commissioners of the Consensus Commission themselves could be entrusted with guiding this reform assembly.

This assembly, free from time pressure, would be responsible for negotiating and reaching agreement on those proposals in the July Charter that currently have dissent or objection, and for implementing them once consensus is achieved.

If we look at Indonesia's latest constitutional reform process, we see that they began in 1999 and, incrementally, they completed the final stage in 2002. In that final, fourth stage, they reached constitutional settlements on highly contentious issues on Sharia law, the Constitutional Court, and provincial autonomy. To preserve national unity, they even allowed their most conservative province to operate under Sharia law. This gradual process of implementation helped bind Indonesia's divided society together.

Bangladesh too must respect its internal differences. Mechanisms must be created to allow opposing groups to keep the dialogue going. With time, such dialogue will eventually produce consensus.

The interim government has taken time to fulfil many of its commitments to ensure the quality of its work. At this critical stage of constitutional reform, if they likewise prioritise quality over haste, the interests of the people will be protected. The signing ceremony of the July Charter may be postponed until a clear roadmap for implementation is agreed upon.

Syed Hasibuddin Hussain, a political activist, who can be reached at hasibh@gmail.com.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments