Will our parties' culture change in poura polls?

Will the partisan elections to the local government bodies open a window for "nomination business" by the major political parties? Is it going to tighten the parties' grips over their grassroots level leaders?

These vexed questions have now come to the fore because of the traditional culture of non-democratic practices inside the parties and allegations of widespread "nomination business" by the major political parties in previous parliamentary elections.

This non-democratic nature of the parties has become the seedbed for the rise of businessmen in our parliamentary politics.

Of the MPs elected in the 1954 election, only four percent were businessmen by profession. The percentage rose to 63 in the 2008 election, thanks to our major political parties' "generosity" towards businessmen.

Once the local government bodies' laws are amended, the political parties could nominate candidates and allow them to use their parliamentary electoral symbols in the local elections to City Corporations, municipalities, zila, upazila and union parishads.

It is not yet clear how the political parties will nominate their candidates to contest the local polls. Will the parties allow their grassroots level units to nominate the candidates or will the central high commands meddle in there? Will money play a role in getting party nominations?

None of the political parties' constitutions contain any provision allowing its grassroots level units to do the task as it was not a requirement before.

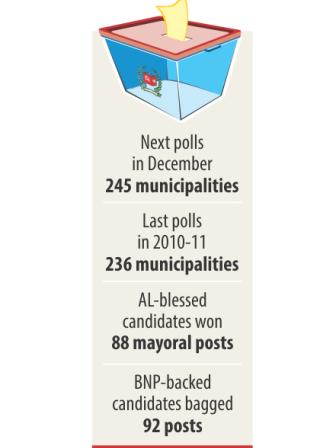

Neither will the parties have the time to change their constitutions to introduce any such mechanism. The government seems to be in a hurry to hold local elections on partisan lines from the municipality polls coming December.

Until now, the political parties could not nominate any candidates and allow them to use their parliamentary electoral symbols in the local polls. They could only extend their support to a particular candidate.

Grassroots level leaders who were not blessed by the parties could however contest the polls. Their parties could not prevent them from contesting the elections and take any actions on charge of violation of party disciplines.

But once the elections are on partisan lines, the parties will have authorities to rein in their grassroots level leaders. This new law may create an unhealthy situation in the local politics, instead of supporting democratic practices at grassroots levels.

The fear of negative developments in local levels is justified. Our political parties could not show the citizens that they were against "nomination business" and wanted to ensure democratic practices within the parties.

It seems that our political parties perhaps like to destroy any good initiative if it goes against their set way of working. The reversal of the electoral reforms done by the past caretaker government meant to pick parliamentary candidates in a meaningful democratic way and end the culture of "nomination business" is a glaring example.

Before the 2008 parliamentary election, a provision was included in the Representation of People Order, making it mandatory for a registered political party to finalise nomination of candidate by its central parliamentary board from the panels prepared by members of the ward, union, thana, upazila or district committees of the party.

This provision had empowered the grassroots level leaders to contest the parliamentary polls. It also curbed the powers of the parties' parliamentary boards consisting of central leaders to pick any parliamentary candidates.

The other reason behind the provision was to ensure democratic practices within the parties by empowering their grassroots level units.

But later, the Awami League-led government weakened the spirit and effectiveness of this provision. It brought back the power to the parties' parliamentary boards again to pick candidates to contest the parliamentary elections.

The changes give the parliamentary board of a party the discretion to consider the grassroots panels in finalising the candidates but it is not mandatory any more for the boards to pick candidates from the grassroots panels.

The government has also scrapped another provision which had made it mandatory for an individual to be a member of a registered political party for at least three years to contest the national elections from that party. This provision was made against those individuals, especially businessmen, who did not do active politics or were not involved in any political party, but joined major political parties just before the polls and bought tickets from them with a huge amount of money. It was aimed at stopping alleged widespread "nomination business" by major political parties in the parliamentary polls.

Former Chief Election Commissioner ATM Shamsul Huda, who led the sweeping electoral reforms in 2008, thinks the same electoral reforms should be introduced in picking candidates to the local polls.

The former CEC says, these reforms will bring qualitative changes in democratic practices in grassroots levels and also be effective in fighting "nomination business."

He thinks "nomination business" may not matter in the union parishad elections, lowest tier of the local government system, because it is closer to the people.

But there is a risk of "nomination business" at the higher levels of the local government bodies like city corporations.

The Election Commission can play a crucial role in bringing some important reforms in electoral laws after the local government bodies' laws are amended.

The EC has the power to make electoral rules to conduct the polls. So, the EC, if it wants, may move to bring some changes in the electoral rules ahead of the upcoming municipality elections to be held in December. If the EC makes any such move, the political parties must come forward to implement the reforms.

The upcoming municipal polls may determine if partisan elections would strengthen our democracy or damage its nature.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments