Understanding Nepal’s Gen Z revolution in a South Asian context

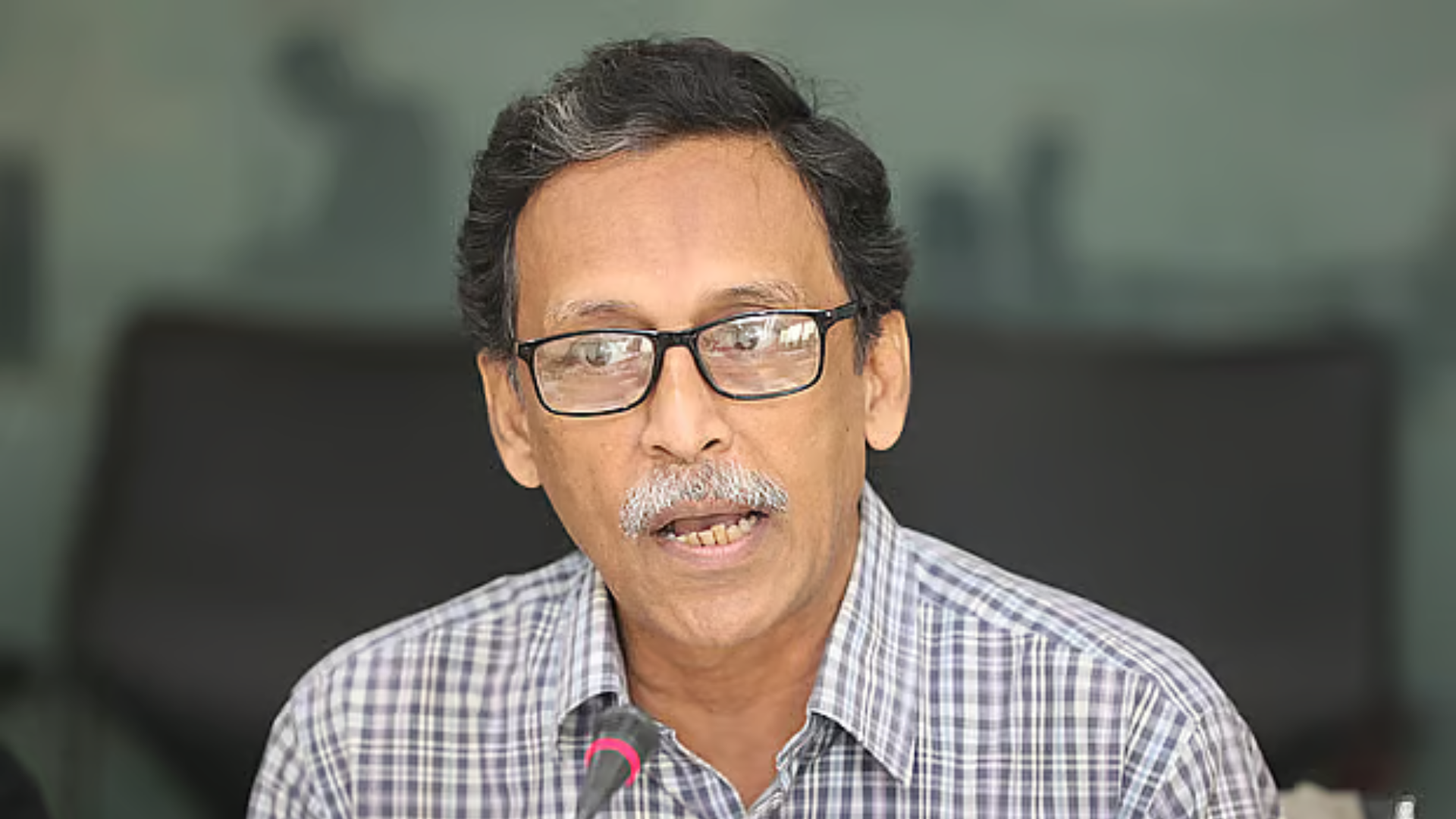

The fall of KP Sharma Oli's regime in Nepal -- echoing similar events in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh -- signals a shifting political tide across South Asia. To unpack the causes and what might come next, The Daily Star spoke with South Asian history researcher and columnist Altaf Parvez.

The Daily Star (TDS): What drove Nepal's Gen Z to rise up and topple the government?

Altaf: The immediate factor was the ban on social media. They were angry about it. They came out to the streets and possibly, using VPNs, accessed those sites and based on that they called for the movement. This was an immediate factor. What was unfolding in Nepalese society, especially among the youth, was a deep sense of political frustration. That frustration was the driving force behind the movement.

That frustration was directed at their political system, particularly at the political parties. Nepal has three main parties -- the Nepali Congress, UML (Unified Marxist-Leninist), and the Maoist Centre, and they have been ruling for almost 20 years since the monarchy was abolished in 2008. The three main leaders of these parties have been rotating as prime minister. The way they have run the country has created deep frustration in politics there. This was mainly the background for the protest.

TDS: Nepal has shifted from monarchy to democracy. Where do pro-monarchy parties and activists stand in this new landscape?

Altaf: They too had the desire and preparation to come out to the streets. In fact, at the beginning of this year, they already had. A large protest had occurred in Nepal, where two people died. But the government managed to control that, because all the main parties shared a consensus in opposing monarchy.

TDS: There was a campaign called "Nepo Kids". What was that about?

Altaf: The movement was essentially a backlash against the lavish lifestyles of politicians, bureaucrats, and their relatives. Young people rose up against nepotism and corruption, highlighting the stark contrast between the lives of ordinary Nepalis -- at home and abroad -- who struggle to earn a living, and the elite, including politicians, judges, bureaucrats, and their children, who enjoy unchecked luxury. This disparity struck a deep chord with the public, and it reflects a pattern seen across South Asia.

TDS: Corruption was clearly a major issue in Nepal. Was it worse than in Bangladesh?

Altaf: In Bangladesh, the bigger problem has been capital flight, which reached epidemic levels. Nepal doesn't face that in the same way. Instead, its corruption is more administrative. Politicians don't hold themselves accountable, and ordinary people are forced to pay bribes or endure harassment just to access basic services. This kind of corruption exists in Bangladesh and across South Asia, but in Nepal it is more pervasive. People had hoped that the shift from monarchy to democracy would resolve these issues, but it hasn't.

TDS: Some groups are now calling for the return of the monarchy. Why is that?

Altaf: This sentiment stems from frustration with how democracy has functioned in Nepal. The monarchy, which lasted 240 years, was deeply entrenched. So much so that even the British, who colonised much of South Asia, could not subdue Nepal. The push for democracy came largely through the armed struggle of the Maoists, which then allowed other democratic forces to emerge. But once democracy was established, successive governments failed to meet public expectations. They couldn't transform the economy, divisions among political parties grew, and governments kept collapsing. As a result, the old influence of the monarchy still lingers, and some groups now see it as an alternative. Nepal has changed governments 13 times between 2008 and 2025.

TDS: Nepal has proportional representation, the same system now being debated in Bangladesh. Is there any issue with that?

Altaf: In one sense, yes; in another, no. With Nepal's new constitution, governance is highly decentralised. So, even if the central government is unstable, local development continues. But people were frustrated because central governments kept collapsing. For example, when parties with fewer seats formed a coalition, the party with more seats was left out. That created voter dissatisfaction. So proportional representation was a factor, but the main issue was unethical government formation and collapse.

TDS: Over the past two days, we've seen massive violence -- government offices, ministers' homes, hotels, even the Supreme Court were attacked. Yet Gen Z leaders insist they were not involved. How do you see this?

Altaf: On the first day, rallies began peacefully, with music. Then groups broke away. Nineteen people were killed. That death fuelled further violence the next day, when groups carried out systematic arson and destruction -- burning institutions. These were not ordinary youths. Suspicion is on pro-monarchy groups, like the Rastriya Prajatantra Party, and also the youth-based Swatantra Party.

TDS: With a power vacuum, which way does Nepal move?

Altaf: There is total uncertainty. The prime minister resigned, ministers fled, the police force in Kathmandu disappeared. Anarchy is prevailing. Meanwhile, the offices of the three main political parties were also burned down. Their leaders are gone. How will government, administration, and judiciary function? The economy is also collapsing. So, the country has entered total uncertainty.

TDS: Bangladesh after the July uprising and Sri Lanka in 2022 both went through periods of turbulence. Do you see any parallels with Nepal?

Altaf: The model of uprisings in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Nepal is almost the same. In Sri Lanka, protesters seized the palace, carried out vandalism. In Bangladesh, there was violence. The same happened in Nepal. The difference in Sri Lanka was that it quickly restored stability under Ranil Wickremesinghe. He revived the economy and law and order. In Bangladesh, economy has not revived to a satisfactory level. Law and order remain a concern. In Nepal, the uprising destroyed the entire political system -- the parties, state machinery, and judiciary. Within 48 hours, these three forces were gone. That's different from Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, where some political alternatives remained.

TDS: Corruption, authoritarianism, inequality, and political failures all seem to have fuelled these uprisings. But was technology also a driving factor?

Altaf: Yes. In all three countries, social media played a central role. Even though mainstream media exists, youths relied on social media. It was a key instrument.

TDS: Do you think external factors had any influence on youth movements?

Altaf: The main drivers were internal, but external factors also had some influence. For instance, on the first day of Nepal's events, a group of countries, including the US, issued a statement in support of the protesters. In addition, many of the social media platforms that played a role are western-owned, with significant business interests. So, while the movements were rooted in domestic issues, outside actors did have a presence in the background.

TDS: What do you see as the strengths and weaknesses of these youth movements?

Altaf: A clear strength is that young people are actively engaged with politics, society, and the economy -- they are not indifferent. The challenge, however, is that they have no alternative model of political systems. In Sri Lanka, after seizing the palace, they couldn't say "what next." In Bangladesh too, traditional politicians quickly filled the gap. The same is happening in Nepal. Gen Z leaders have mobilised effectively, but they haven't yet presented a clear plan for running the country.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments