The persistent problem of plastic pollution

This year at the UN Climate Change Conference, Bangladesh played an important leadership role as the head of the Climate Vulnerable Forum (CVF), pushing for greater accountability from big pollutants and fighting for climate action on the global stage. As a country that is already bearing the brunt of the climate emergency—despite contributing to less than 0.5 percent of global emissions—we not only have the moral authority to speak out, but have also led the way with actions like the creation of the Mujib Climate Prosperity Plan. By all accounts, Bangladesh remains a respected and important player in climate diplomacy circles.

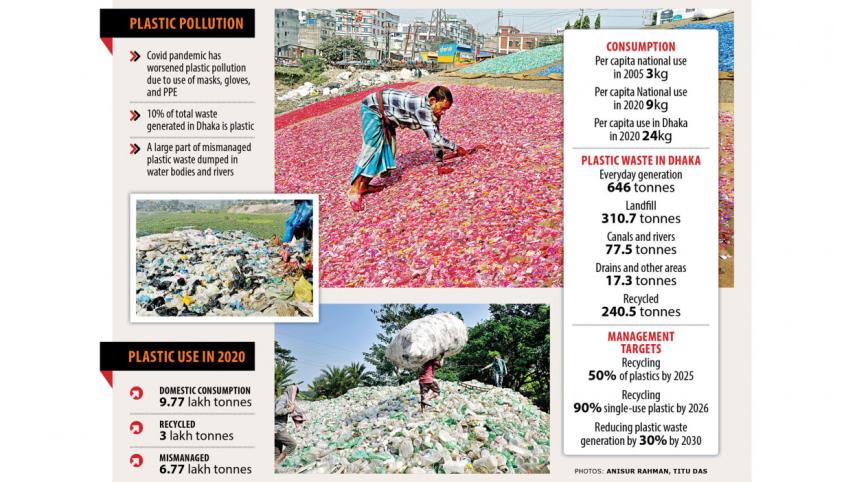

However, climate change and environmental pollution are two sides of the same coin, and in minimising the latter, Bangladesh's performance has been woefully inadequate—if not downright negligent. This is especially the case in terms of overconsumption of plastic and mismanagement of plastic waste. While globally there is a push to reduce plastic consumption, in Bangladesh's urban areas, it has tripled in 15 years (between 2005 and 2020), according to a World Bank study. Of the 977,000 tonnes of plastic consumed in 2020, only 31 percent were recycled—the rest ended up in landfills, rivers, canals, drains and unserved areas.

The sorry state of our rivers is testament to the crisis that has been created by our apathy towards plastic pollution. In March this year, it was announced that the cost of dredging the Karnaphuli River had increased by Tk 49 crore (19 percent) due to the removal of a thick layer of plastic waste from the riverbed. Dredging operations to remove silt from Barishal river port also dragged on for months due to the huge amounts of polythene and plastic dumped into the water. Every year, about 200,000 tonnes of plastics flow into the Bay of Bengal from Bangladesh, having far-reaching consequences not only on marine life, but on human health, too, as a result of microplastics seeping into our ecosystem.

How can a country that is well-known for its climate diplomacy—and for taking progressive steps such as banning the use of polythene bags as far back as in 2002, and banning single-use plastics in coastal areas in 2020—still have such recklessly high levels of plastic pollution? It is clear that, so far, the government has failed to match its policy with suitable actions. This cannot be allowed to continue—the authorities must ensure that they stick to the National Action Plan for Sustainable Plastic Management in order to reduce plastic waste generation and recycle as much as possible.

At the same time, there must be a concerted push to use alternatives to plastic packaging. Bangladeshi scientists have already invented jute polymer packaging and biodegradable packaging materials from corn. We have all the resources at hand to reinvent ourselves from being one of the worst plastic-polluting countries in the world to one that brings its own sustainable solutions to global platforms. It is now up to the authorities to demonstrate their commitment towards this end, and act accordingly.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments