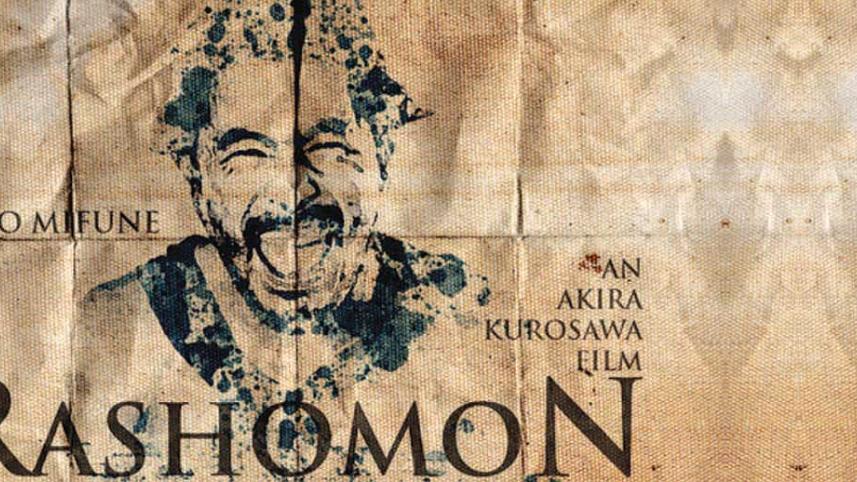

Rashomon: More than just a cinema

In 1923 at the age of 13 he went with his elder brother Heigo to see the devastation of the Great Kanto earthquake that brought Tokyo and Yokohama to their knees. He turned his eyes away. Heigo forced him to look. The experience left an imprint in the mind of the young Akira Kurosawa (1910-1998). He went on to confront truth and reality in his movies. The 1950 classic “Rashomon” not only put Japanese cinema on the world map, it addressed two questions that have puzzled men forever: What is truth? What is reality?

A woodcutter and a priest sit beneath the Rajomon city gate as the rain pours. A commoner joins them. The woodcutter tells them how he found the dead body of a samurai while cutting wood in the forest. The priest says he saw the samurai and his wife the same day the murder happened. Thus the story starts.

The absolute is clear. The samurai died. There were two direct witnesses: the bandit and the samurai's wife. The court hears the views of all three. They hear the samurai through a spirit. The court also hears the story of the woodcutter who reported the incident to the authorities and who seemed to be the least unbiased.

At first, the four different narratives resemble the ancient story from South Asia of the blind men and the elephant. Each blind man touches one part of the elephant and narrates his own story. Each blind man sees only one part of the whole elephant. Thus each narrative is a part of the whole truth. The story reminds us that the whole truth is almost impossible to find.

“Rashomon” is different. Each character (except the woodcutter) is a direct witness to the same event. They all see the same event from beginning to end. Yet all three and the woodcutter provide narratives that conflict each other. As the story unfolds and each narrative is presented, it's difficult not to ask what the actors themselves asked Kurosawa during the making of the film: 'What is the truth?'

Why do different people see the same event differently? Like a camera our minds have more than one focal point. When we look at an event, we tend to look through one focal point. Looking through more than one focal point at the same time can be difficult, but more importantly we don't want to look through more than one focal point. This is what Kurosawa addresses in “Rashomon” through his camera.

When scientists analyse a problem, they usually don't have a direct interest in the problem. They observe like a 'fly on the wall'. When we have a personal interest in a problem, we don't see the whole event through all the focal points available to us. We become biased and form our own view and present it the way we think is best based on our personal conceptions.

Think about an event. Team A defeats Team B in a game. The next day you read the newspapers. You see two different and conflicting versions of the same game. What you observe is the personal interest of the narrator and how they present you the game as it happened. Reality is based on the perspective each narrator takes in their description. “Rashomon”, however, goes one step ahead.

Art transcends boundaries when it becomes a 'fly on the wall' observation. In the end we appreciate the final message. Sixty-five years since it was made, “Rashomon” reminds us that when we can rise above personal interest, vanity and pride, we see like a 'fly on the wall'. We see the truth. If you haven't seen “Rashomon”, you probably haven't made that personal journey to search for truth.

Asrar Chowdhury teaches economic theory and game theory in the classroom. Outside he listens to music and BBC Radio; follows Test Cricket; and plays the flute.

He can be reached at: asrar.chowdhury@facebook.com

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments