The struggle against concrete invasion

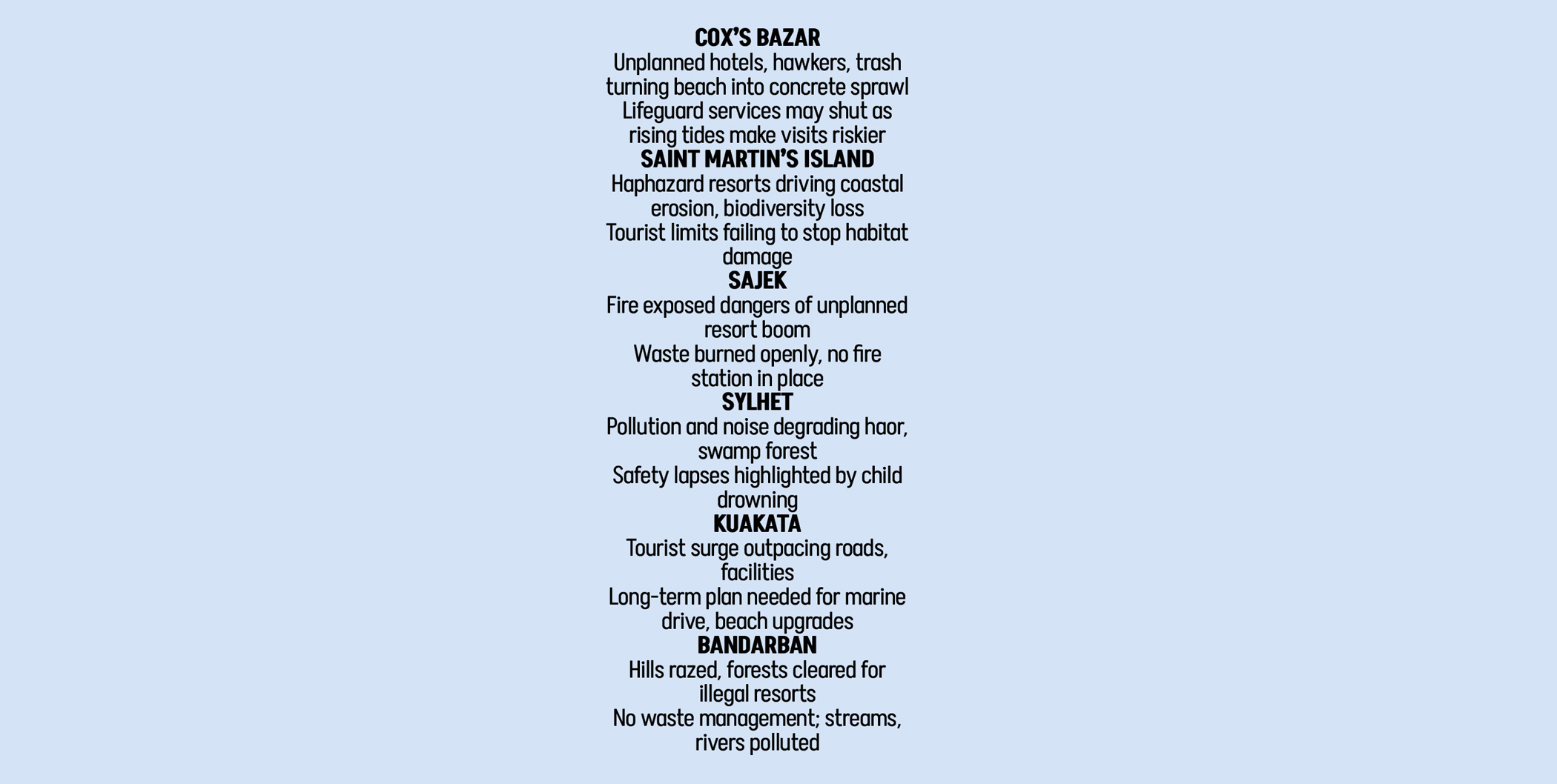

From the beaches of Cox's Bazar and Kuakata to the hill slopes of Sajek Valley and the wetlands of Sylhet, Bangladesh's major tourist destinations are expanding without proper planning or regulation.

Makeshift shops, unauthorised hotels, risky embankments, and unregulated boating threaten the environment, tourist safety, and long-term sustainability.

Experts and stakeholders warn that unless coordinated master plans are enforced, the country's most attractive sites risk losing their natural beauty and appeal.

Cox's Bazar

Arif Khan, who travelled from Dhaka's Bashundhara area with his wife and two children, was roaming around Cox's Bazar sea beach. Asked whether the area was tourist-friendly, he said nothing appeared to be developed in a planned manner.

"Shops have sprung up everywhere, making it hard to walk because of hawkers. Umbrellas are lined up across the shore, blocking tourists' movement."

At Sugandha point on Friday, he saw nearly thirty thousand people, most of them entering the sea but with no modern changing rooms or proper shower facilities. "A few shabby sheds offer bathing and toilet services, but the condition inside is so poor no one wants to use them."

He also pointed out that there is no control over rentals. "Vehicle fares and hotel rents are unusually high. The money one spends in Cox's Bazar could easily cover a foreign trip."

Hasem Ali, a businessman from Dhaka's Sutrapur, said the main beaches -- Sugandha, Kolatoli, and Laboni -- become unsafe at night. "Even nearby areas feel risky, and the isolated spots in the hotel-motel zone are not safe for tourists," he said, urging stronger security.

"People come here seeking open spaces, but the congested hotel-motel zone is no different from the city. Cox's Bazar has a 120-kilometer beach, so why are all the hotels crammed into just a few kilometers?"

Nasima Khatun, a homemaker from Bogura, compared her visit with Thailand. "There, you find beautiful walkways and sitting areas by the beach, but there is nothing like that here. The Marine Drive is attractive, but it takes a long journey to reach."

A visit to the three beach points revealed countless makeshift shops, their numbers growing daily. On social media, many have compared these tarpaulin-covered stalls to Rohingya camps.

Abu Morshed Chowdhury, president of Cox's Bazar Chamber of Commerce, said tourism has not developed in a planned way. "The city is turning into a prison of brick and concrete. If unplanned hotel construction continues, Cox's Bazar will lose its charm. Waste management is absent in the hotel-motel zone, and untreated garbage is dumped into the sea, creating a public hazard."

Mukim Khan, general secretary of the Cox's Bazar Hotel Owners Association, said roads in the hotel-motel zone are in terrible condition. Construction drags on for years, and during the monsoon tourists suffer greatly. With proper planning, he said, the industry could serve tourists better and grow further.

Sea Safe Lifeguard, which provides services at Cox's Bazar beach, is on the verge of shutting down due to a funding crisis.

Regional manager Imtiaz Ahmed said that without new funding, they would be forced to suspend operations from October 1. "Due to climate change, tidal waves have grown higher during the monsoon, causing erosion and putting tourists' safety in danger."

Abul Kashem Sikder, president of the Cox's Bazar Hotel and Guesthouse Owners' Association, said that about six million tourists visited in 2023, seven million in 2024, and the number is expected to exceed eight million this year. "Although numbers rise every year, no new entertainment facilities or amenities are being developed."

Chowdhury of the Chamber of Commerce added that there is no accurate data on tourist numbers -- a key obstacle to building a planned industry.

Saint Martin's Island

Unplanned expansion is also visible on Saint Martin's Island, where over 200 hotels and resorts have sprung up haphazardly. Experts warn that the island's biodiversity is under severe threat.

The government allows only 2,000 tourists daily, restricts overnight stays, and limits services to two months a year, but excessive influx has already caused biodiversity loss.

Abdul Aziz, an environmental activist, said hotels and resorts built along the coast have accelerated erosion. He alleged that resort owners cleared coastal bushes that once protected the island and that unplanned geo-tube installations have worsened the situation.

Sajek

For years, Sajek Valley in Rangamati has been filled with unregulated resorts and cottages. The risks became clear on February 24 this year, when a massive fire destroyed around 95 structures, including more than 30 resorts.

After the incident, the Rangamati Hill District Council announced that no new establishments can be built without its approval. In August, it began issuing licenses and design approvals. So far, 72 resort owners have received licenses, with others still in process.

Resort owners welcomed the move. Indra Chakma, owner of Sajek Hill View Resort, said, "Now that we have licenses, running our business will be easier. Earlier we just paid revenue, there was no formal system."

Council Chairman Kajol Talukder told The Daily Star, "Unplanned construction has spoiled Sajek's beauty. From now on, anyone wanting to build must obtain approval, and no structure taller than two stories will be allowed."

Locals said waste management is poor, with most of it burned. Pranto Roni, of CHT's Nature and Biodiversity, said emphasised the struggle to tackle plastic waste. "The impact may not be immediate, but it will appear in the future. A proper waste management plan is urgent."

Despite the devastating fire, no fire service station has yet been established in Sajek.

Sylhet

Sylhet's natural gems -- Tanguar Haor, Jaflong, Ratargul Swamp Forest -- are under stress from unplanned tourism. Water pollution, plastic waste, loud noise, and unregulated boating threaten breeding grounds and rare species.

On August 15, five-year-old Masum Miah drowned while visiting Tanguar Haor on a houseboat with his family.

No accurate data exists on tourist numbers, according to multiple sources.

Kuakata

Since the opening of the Padma Bridge, tourist numbers in Kuakata have surged. But weak infrastructure and unplanned urbanisation continue to hold back the beach town's potential as a modern hub, locals alleged.

Bandarban

Unregulated tourism is rapidly expanding across Bandarban's hills, raising concerns of environmental degradation and biodiversity loss.

In recent years, areas around Nilgiri, Nilachal, Merinja Valley, Nafakhum, and Boga Lake have seen mushrooming resorts and entertainment centres. Environmentalists warn that most lack permits or environmental clearance.

Zuam Lian Amlai, president of the Hill Forest and Land Rights Protection Movement Committee, said, "Before building any structure in such a fragile environment, environmental impact assessments must be carried out. Instead, hills are being cut and forests cleared in the name of tourism. This is disastrous."

Residents allege that unchecked growth is damaging waterfalls, streams, forests, and wildlife habitats.

Rezaul Karim Chowdhury, assistant director of the Department of Environment in Bandarban, told The Daily Star that none of the spots have environmental clearance.

"Resorts and hotels have been built without waste management. Waste is dumped directly into hills and forests, eventually flowing into rivers, harming biodiversity. Due to manpower shortages, we cannot conduct regular drives."

He warned, "If planned measures are not taken immediately, Bandarban's tourism sector will face a crisis. Both the environment and economy must be protected together."

Lama Upazila Nirbahi Officer Mohammad Moin Uddin told The Daily Star that around 80 spots have emerged in Lama upazila, including Merinja Valley. "While some have permits, many do not. We are urging owners to obtain approval, but several are still building on hilltops without clearance. Waste, including plastics, is being dumped indiscriminately, posing a serious threat."

Bangladesh's most treasured landscapes are being consumed by unchecked tourism. Without urgent planning, strict enforcement, and sustainable practices, the country risks trading its natural wonders for concrete sprawl and polluted waters.

The choice is clear: either protect these fragile ecosystems now or watch them vanish.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments