Hair, humiliation, and madness: The policing of bodies

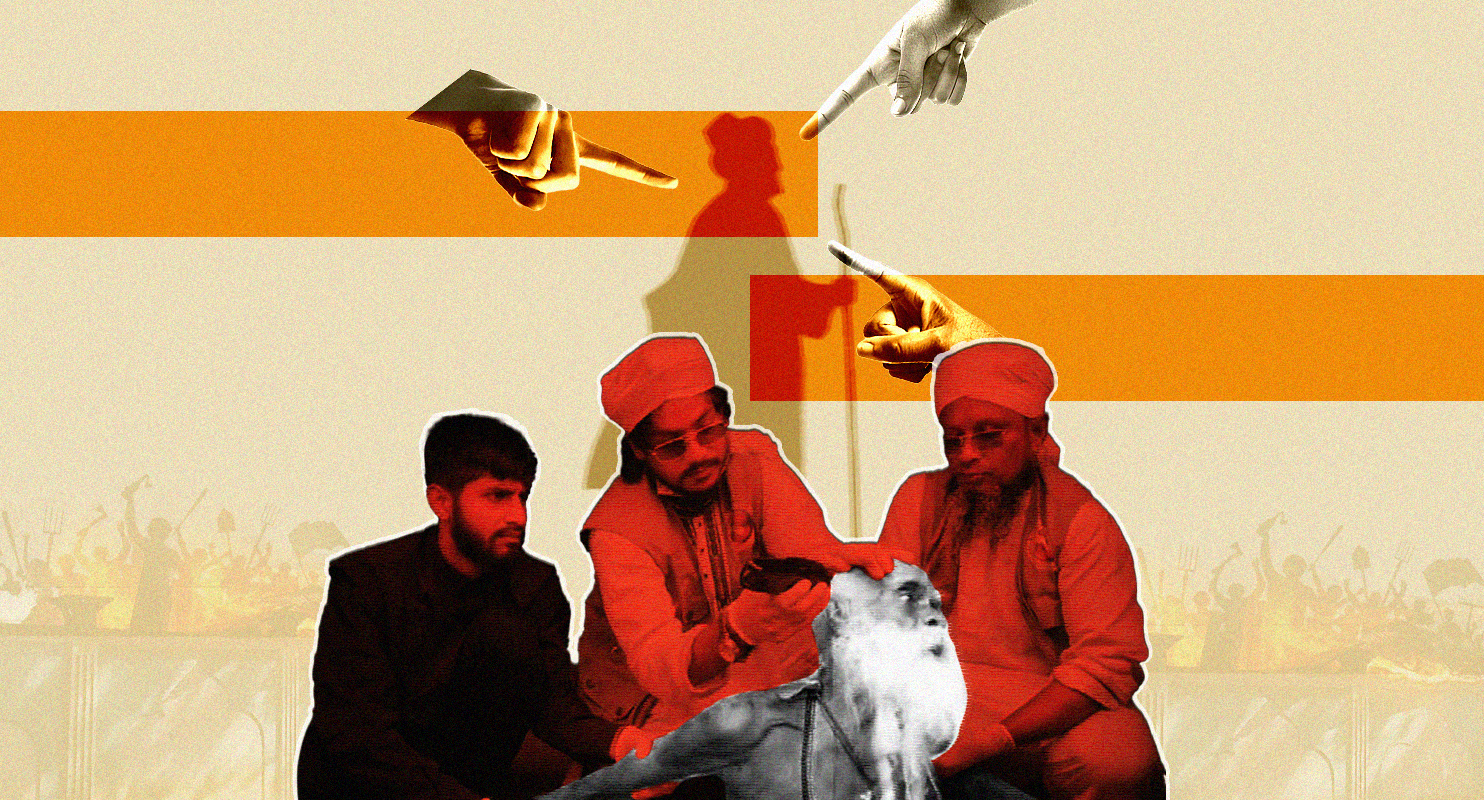

A recent video circulating on social media shows three men holding down a 70-year-old man named Halim Uddin Akand and forcibly cutting his dreadlocks in the name of social service. Halim Uddin claims to have been growing his hair for nearly four three decades after visiting the shrines of Sufi saints Hazrat Shah Jalal (RA) and Hazrat Shah Poran (RA). As the deeply troubling video unfolds, the Mymensingh native can be seen crying to the Almighty, "Allah, tui dehis!" ("Bear witness to this, Allah.")

Much has already been written about this incident, critiquing the moral, religious and ideological policing that it reflects. Our interest in this vile act of coercive hair-policing, however, is twofold. On the one hand, we reject this kind of vigilantism against bodies and peoples, irrespective of their faith and value system, in a post-uprising Bangladesh. On the other hand, we want to interpret this particular incident through the historical lens of other forms of hair-policing that tend to target the vulnerable in our society, particularly women. We address the question: how could this particular video be placed within the narratives of hair, its policing and politics? Can women's and men's hair be placed within the same contentious framework of religio-patriarchal dominance?

Hair, one must acknowledge, shapes much of the narratives pertaining to womanhood, widowhood, modesty, sexuality, social ostracism and more within the context of South Asia. Consider the image of a Bangalee Hindu widow in popular culture and literature, her head forcibly shaved after the passing of her husband, desexualising and dehumanising her for the rest of her life. The widow's hairlessness serves as a constant reminder of a woman's social status being inextricably tied to her hair. Consider also the pressures women in contemporary Bangladesh face—in our cities, villages, institutions, public spaces, and even within private domains—regarding how, and in what precise way, their hair is visible, concealed or sexualised. It is no exaggeration to claim that how a ghomta is worn, what form of hair covering is being practised, when hair can be let loose, and in whose presence, are questions and concerns that women and girls of this region must negotiate constantly, even daily. Some businesses insist that their staff must cover their hair, some schools encourage it, and the general public freely shames and polices women for their hair (un)covering or (in)visibility practices. Women's hair choices, thus, are incessantly monitored, surveilled, and often enforced. Hair is deeply political, and its regulation is not exclusive to South Asian or Bangalee female lives. Orthodox Jewish women, for example, are required to shave their heads and wear wigs after marriage to deter desirability from other men. Covering and uncovering hair is where societal "certification" is awarded.

Post-9/11, much global attention has been placed on Muslim women's right to cover, as well as the enforcement or removal of their headscarves. Recall the US's call to invade Afghanistan under the pretext of "rescuing women in cover" from the Taliban, as though a debilitating war against an entire people could somehow be framed as a feminist mission. Considering the state Afghan women find themselves in, 20 years after the US left, the facile and, frankly, racist nature of that claim could not be more obvious. Curiously, Western feminism's embracing of the headcover as an empowering garment also remains a partial truth to the larger Muslim hair-covering narrative. Of course, just as one cannot be forced to cover their hair, one cannot be forced to remove their hair covering either. So much depends upon female hair—from empowerment to coercion, from religious indoctrination to resistance, and from social mobility to power. It is within this framework that we situate the forcible hair-chopping of Halim Uddin Akand.

A devotee of Shah Jalal (RA) and Shah Poran (RA), Halim Uddin's uncut hair testifies to Bengal's intrinsic plurality of faith. His long, uncut hair bears witness to the blending of Sufi traditions, Bengal's spiritual conventions and tarika, fakiri, and, more simply, an individual's autonomous choice to adorn their body as they decide. The cutting is part of the dangerous trend of attacking the sites of pluralism in the post-uprising Bangladesh, including mazars, akhras, and khankas, rejecting some of the very ideals the movement stood for. This forcible hair-cutting act is not merely about personal appearance but about policing identity, stripping away markers of belonging that do not conform to an exclusionary vision of faith. In doing so, the three men situate themselves within a broader project of erasure, where difference is not tolerated but eliminated.

Halim Uddin's pagol (madman) status is also uniquely familiar to us as Bangalee. Historically, women have been labelled daini (witches), rakkhoshi (monsters), and indeed, pagli (madwomen) whenever they did not conform to social norms or could not be contained by hegemonic frameworks. But history also reminds us that in Bengal, pagol were torchbearers of courage and resistance. Under Karam Shah Pagol and his son Tipu Shah, the Pagolpanthis of Mymensingh and Sherpur rose to become one of the first organised challenges to colonial power and zamindari oppression. In 1825, Tipu Shah's followers captured Sherpur and established a just administration with lower taxes, creating an independent nation of peasants (Gautam Bhadra, Iman o Nishan). It was a visceral jolt for the British administration. By 1833, the rebellion was crushed, and Tipu Shah was sentenced to life imprisonment. Local legend holds that Tipu Shah Pagol will return on a full moon to the banks of the Kangsha River. The eternal life of the pagol on the banks of the Kangsha River does not die.

Since then, the word pagol has metamorphosed in the hands of oppressors. Once a title given to the knowledgeable and wise (think of Lalon's tin pagoler hoilo mela), it has been turned into a tool to otherise and dehumanise bodies that do not conform to power. Irrespective of gender, once the pagol label is attached to someone, it clings to the bodies of the subjugated, questioning their very humanity, as seen in the case of Halim Uddin. His spectacularised hair-chopping thus can be read as an act of patriarchal disciplining, a violent attempt to erase difference, and a continuation of branding the resistant as "mad" to strip them of dignity and legitimacy.

Indeed, a quick Google search reveals multiple incidents of forcible hair-cutting and its resulting humiliation in recent months: in June, a woman's head was shaved over dowry demands in Lakshmipur; in July, another woman in Gaibandha was shaved and stripped naked for an alleged extramarital affair. Earlier in March, a 19-year-old young man took his own life after a union parishad member forcibly cut his hair to publicly shame and discipline him. These acts are not isolated; they reflect a broader pattern of using bodily humiliation to enforce social control and punish those who defy hegemonic norms. The psychological and social consequences of such violence can be long-lasting, instilling fear and reinforcing oppressive power structures within communities.

We wonder how long the state will remain apathetic in the face of such brutality. While it is encouraging that two arrests have been made in connection to Halim Uddin's case, we cannot ignore that repeated acts of violence make all of us—women, children, bauls, the poor, and pagol—vulnerable. Every cut, every humiliation, is an attack on our shared humanity, and ignoring it only strengthens those who thrive on fear and control. Silence is complicity; courage and collective action are the only antidotes to the cruelty that seeks to divide and dominate us.

Dr Nazia Manzoor teaches English at North South University and is editor of Star Books and Literature at The Daily Star. She can be reached at nazia.manzoor@gmail.com.

Sharmee Hossain teaches English at North South University. She can be reached at sharmeehossain28@gmail.com.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments